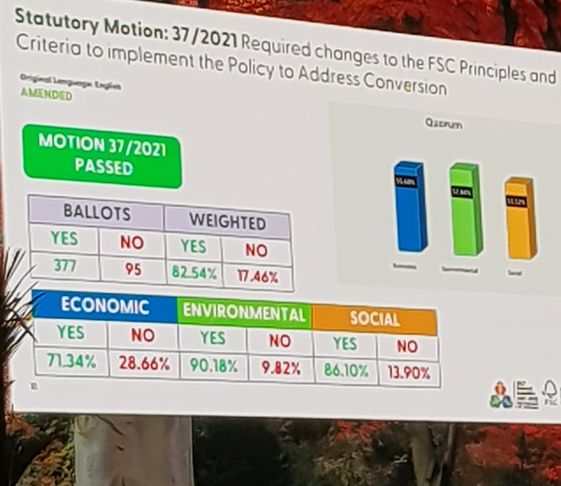

The FSC General Assembly 2022 has just ended, with 14 motions passed and approved by a majority of the members. Two of these were of great significance to Indonesia: Motion 37, regarding changes to the conversion policy, and Motion 45, regarding remedies as compensation for conversion. Both are linked to the four FSC policy packages that allow plantations on areas of natural forest converted between 1994-2020 to be certified under the FSC scheme.

After I joined FSC in July 2013, people frequently asked me the same question: “What are the challenges for FSC in Indonesia?”. My answer was always the same: “The difficulty of certifying plantation forests in Indonesia.” These plantations were generally established after the 1990s through the conversion of natural forests.

I quickly found that it was necessary to counter the myth that plantation forests could never become FSC certified in Indonesia. I had to convince plantation forest managers that while it is not easy to certify plantations, it is possible. I told them their plantations could be certified in certain cases – for example, those established before 1994, or those where the current forest manager was not the one responsible for the conversion.

The certification of plantation forests on the island of Java managed by Perum Perhutani was a good example. Established more than a hundred years ago, the plantation now has nearly 500,000 hectares certified, and more growth is expected. Outside of Java, things are admittedly still difficult, since these plantations were all established after 1994.

But the possibilities is there. In 2017, the first plantation forest outside Java, in Central Sulawesi, had 74,000 hectares certified by FSC. This did not last long, because the plantation was still under establishment and had not yet produced any timber. The certification was terminated in 2021. But before that, in 2020, PT Hutan Ketapang Industri in West Kalimantan had 97,000 hectares certified by FSC. Interestingly, the main product of this plantation is latex and not wood.

Now I would like to discuss motions 37/2022 and 45/2022, and the policy package which includes Policy to Address Conversion, Policy for Association, Remedy Framework, and the Disclosure Requirements for Association with FSC Procedure, shortened to CARD – short for “conversion, association, remedy and disclosure”.

These motions and policies do not represent a free pass nor a “red carpet” for those who have converted natural forests in the past and created negative environmental and social impacts. But they do represent a way in which plantation forests in Indonesia can become FSC-certified. This is not an easy process, and CARD does not aim to present a barrier, but rather a path to ensuring that the impacts of past natural forest conversions are remedied and those responsible are held accountable. We want FSC-certified plantation forests to contribute to forest restoration and social restitution, allowing these plantations to create environmental, social and economic benefits.

The next challenge will be how to fully implement CARD in Indonesia, especially the Remedy Framework, given the enormous variations in type, size and condition of Indonesia’s forests and social. It will be interesting to see how much forest in Indonesia can become FSC-certified through the CARD policies package.

General Assembly 2021-2022 highlights: https://ga.fsc.org/en